Launched in July 2021 at Generation Equality Forum, the Compact on Women, Peace and Security and Humanitarian Action (WPS-HA Compact) is an inter-generational, inclusive movement for bold action on gender equality and to advance the leadership and protection of women and girls in crisis and conflict affected situations. Building on existing mechanisms and expertise, the Compact seeks to achieve transformative progress through action to address gaps and challenges on women, peace and security and gender-responsive humanitarian action.

Peace is inextricably linked with equality between women and men and development.

– Art 131, Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995)

In 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BPfA) was adopted, with women in armed conflict identified as a critical area of concern. Five years later, United Nations Security Council resolution 1325 on women, peace and security was adopted. The year, 2025, will mark the 30th and 25th anniversaries of the BpFA and Resolution 1325, respectively.

In 2021, the WPS-HA Compact was launched with 120 signatories. As of August 2024, there has been a 90 per cent increase to 228 signatories.

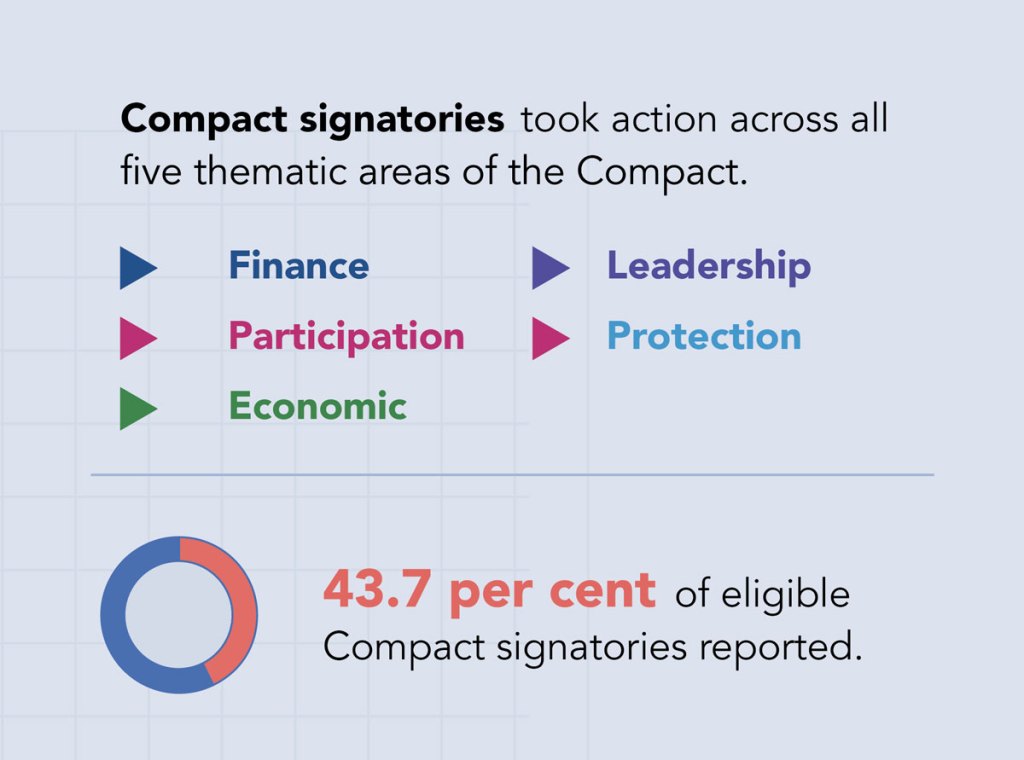

86.6 per cent of the Compact Framework has been committed to and 115 out of 134 actions are being implemented by signatories across all 5 thematic areas.

The WPS-HA Compact has six stakeholder groups including Member States, regional organizations, United Nations entities, civil society organizations, academic and research institutions and the private sector.

In 2021, the WPS-HA Compact was launched with 120 signatories. As of August 2024, there has been a 90 per cent increase to 228 signatories.

86.6% of the Compact Framework has been committed to and 115 actions are being implemented by signatories across all 5 thematic areas.

The WPS-HA Compact has six stakeholder groups including Member States, regional organizations, United Nations entities, civil society organizations, academic and research institutions and the private sector.

612 million women and girls lived within 50 kilometres of at least one of 170 armed conflicts, an increase of 41 per cent since 2015.B This was the fifth consecutive year that peace declined.

The United Nations verified 3,688 incidents of conflict-related sexual violence, a 50 per cent rise since 2022, with women and girls making up 95 per cent of survivors.

Globally, women’s participation in formal peace processes is lagging, with only 19 per cent of delegates, signatories, observers, and mediators being women in 2023 in United Nations-led, co-led and supported peace processes.

Military spending reached $2.4 trillion in 2023, marking the ninth consecutive year of increase.

Despite growing humanitarian needs, from 2021 to 2022, total humanitarian official development assistance dropped from US$ 24.3 billion to US$ 20.8 billion.

Total amount of money spent by signatories.

Total amount of women and girls reached.

CSO: civil society organization; MS: member state; Acad: academic/ research institution; UN: United Nations entity; PS: private sector; RO: regional organization

A lack of adequate, sustained, and flexible funding has been a serious and persistent obstacle to the implementation of commitments to women, peace and security and the empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian action.

The amount spent by signatories to implement their overall Compact actions under this pillar was approximately US$ 1.2 billion, accounting for the highest proportion of spending on Compact thematic areas.

Germany and Canada were the highest contributors to local women-led organizations working in conflict prevention and resolution, including in the context of climate security. Collectively, United Nations Member States allocated at least US$ 1 billion in 2023, with additional funds allocated to United Nations entities to support women-led organizations globally.

The effectiveness of pooled fund mechanisms to support women and girls in conflict and crisis settings was demonstrated by the progress made by United Nations signatories in 2023. The Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) allocated 47 per cent (US$ 95 million) of the Fund’s investments for gender equality and women’s empowerment and exceeded its 30 per cent allocation target for the seventh year in a row. In addition, the Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF) mobilized up to US$ 45.8 million, the largest amount of funds since its establishment in 2016.

Reporting on financing represents 15 per cent of all reporting received on the Compact Framework.

The world has become less peaceful, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index. The average level of global peacefulness deteriorated by 0.56 per cent, indicating the fifth consecutive year that peace has declined.[1] In 2023, global military expenditure increased for the ninth consecutive year marking a 6.8 per cent increase, and largest year-onyear increase since 2009, reaching a total of US$ 2.44 trillion.[2] The decline in global peacefulness and the increase in military expenditure impacts the ability to combat the increased vulnerabilities of women and girls and the aspirations of the Compact on Women, Peace and Security and Humanitarian Action (WPS-HA Compact). Increased militarization can also create environments that are less conducive to women’s involvement in peace processes, marginalizing their voices and perspectives.

The number of people in need of humanitarian assistance has grown considerably with 363 million people in need in 2023. With heightened impacts of crises on women and girls due to gender discrimination and inequality, these proliferating humanitarian crises – including Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, the Occupied Palestinian Territory and many more – are unfolding as deeply gendered crises, with women and girls facing unmet needs, leading to greater vulnerability to genderbased violence (GBV), sexual exploitation and abuse, loss of livelihoods, limited access to resources or access to humanitarian services across the cluster system.[3]

million people were in need of humanitarian assistance in 2023

Military spending reached US$ 2.44 trillion in 2023

Finance ministers from Sierra Leone and Somalia, Uganda’s gender minister, IMF, AfDB discuss financing for WPS NAPs and the WPS-HA Compact. © UN Women/Tanzania

The total financial investment towards the implementation of WPS-HA Compact actions in 2023 was approximately US$ 1.5 billion. The amount of funds spent under this pillar was US$ 1.2 billion or 80 per cent of the total funds spent by signatories. Member State signatories reporting under this pillar included Austria, Australia, Canada, Estonia, Ireland, Germany, Luxembourg, Mexico, Sierra Leone, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates, Uruguay and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Member States reported over 60 per cent of the data of financing WPS and gender-responsive humanitarian action while they represent 39 per cent of signatories reporting on financing.

MS: member state; CSO: civil society organization; UN: United Nations entity; Acad: academic/ research institution

Workshop in Ukraine on crisis communications, cybersecurity and conflict-related sexual violence. © Global Network of Women Peacebuilders

1 Signatories should establish clear, quantifiable metrics and markers for measuring the impact of financial contributions on WPS and humanitarian action initiatives and to ensure that funds are reaching intended target groups including women-led and youth-led organizations. This could be through regular reporting mechanisms that link financial inputs to specific outcomes, providing transparency and accountability.

3 Signatories, including donors and multilateral organizations, should adopt measurable strategies and policies to prioritize sustained increases of ODA dedicated to gender equality and women’s empowerment in line with the United Nations proposal of 15 per cent of ODA. Specifically, in fragile contexts where it has been stagnating and implement more effective methods of integrating gender-responsive humanitarian funding.

SIGNATORY

In 2023, Canada stood out as a leader in financing WPS initiatives linked to its Compact commitments, reporting the second highest allocation of funds among Compact signatories – an investment of CAD$ 453 million. This financial commitment is designed to drive transformative change and deliver tangible results, including in situations of conflict and crisis.

Central to this commitment is Foundations for Peace (2023-2029) the renewed NAP on WPS of Canada, now in its third iteration. The development of the new NAP, launched in 2023, was a meticulous two-year process. According to Nicole Johnston, Senior Policy Advisor at the Coordination Hub for Canada’s National Action Plan for WPS, within Global Affairs Canada, the NAP design centred around the Compact’s principle of multi-stakeholder and inclusive leadership. Extensive engagement was undertaken with 10 federal partners, local and global civil society organizations, women peacebuilders, Indigenous Peoples and other countries with NAPs. This inclusive approach ensured that the NAP is both adaptive and focused on promoting the type of flexible funding demanded by local organizations.

“One of the key takeaways was the necessity for adaptability and flexibility in our approach. We needed to ensure that our NAP could swiftly respond to emerging crises and the changing nature of security threats,” said Johnston.

The new NAP of Canada marks a significant departure from previous approaches, emphasizing qualitative indicators and feminist monitoring practices over traditional quantitative metrics. This shift aims to provide a deeper understanding of the real-world impact of investments, ensuring that funds generate substantial, measurable progress.

“It’s not just about the amount of funding, but also how we fund. Streamlining the processes for proposals and funding agreements, ensuring that monitoring is responsive to the needs of local organizations advancing WPS, and enabling funding that is more risk-tolerant and flexible are crucial,” Johnston explained.

Canada is increasing financing for WPS initiatives.

In 2023, the Women’s Voice and Leadership program was renewed with a funding commitment of CAD $195 million over five years and an ongoing commitment of CAD $43.3 million annually thereafter. This renewed initiative is intended to empower women’s rights organizations, applying an intentional and intersectional approach to reach the most structurally excluded, including LBTQI+ groups and women human rights defenders in crisis and conflict-affected settings. It will provide them with financial flexibility to respond to emerging challenges and opportunities in their communities.

The Canada Fund for Local Initiatives further underscores the commitment from Canada. Supporting 266 WPS projects through a total contribution of CAD$ 9.6 million across 59 countries in 2023–2024. This translated into resources for 348 small women’s rights organizations that operate on the front lines of conflict and crisis, highlighting the focus from Canada on impactful, localized change.

In addition, the financial strategy of Canada includes substantial support for the WPHF and the Equality Fund which allocated CAD$ 21.9 million to 126 women’s rights organizations in 2023–2024 through the support

of Canada and other international donors.

Johnston noted that the commitment from Canada extends beyond international borders to address domestic challenges. The NAP’s new iteration includes a focus on localization – another of the Compact’s principles of transformation – supporting women’s rights organizations and peacebuilders both abroad and at home.

The new NAP deepens its focus on domestic issues, including by addressing the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ People– a situation recognized as an ongoing genocide within Canada. This focus underscores the relevance

of applying the WPS agenda to critical issues at home while supporting similar efforts internationally.

Despite this historic financial commitment, challenges persist. In Canada, efforts to mainstream WPS have led to the integration of funding for WPS in planning and budgets of respective federal partners. However, there is an ongoing call for additional resources specifically earmarked for the NAP, and globally, we see that uncosted NAPs without a dedicated budget experiences challenges in aligning financial resources with strategic priorities, Johnston says.

Still, unprecedented investment from Canada in WPS represents more than a financial milestone; it embodies a new paradigm for how nations can support women and girls in conflict and crisis situations. By prioritizing flexible funding, inclusive design and rigorous evaluation, Canada is setting a powerful example

for the international community.

Out of five thematic areas, signatories allocated the fourth-highest amount of funding (approximately US$ 46.5 million) to participation in peace processes. Though accounting for only 3 per cent of signatory funding across thematic areas, this investment underscores the signatories’ commitment to enhancing women’s roles in peace processes through support for advocacy, programming, support to local women’s networks and financial support.

There is still a huge gap between expressed commitments to women’s full, equal and meaningful participation and progress in practice. This includes processes (co)led and/or supported by the United Nations and those led by other actors. Figures on women mediators, negotiators and signatories have evolved but remain strikingly low. Ahead of the twenty-fifth anniversary of resolution 1325, Compact signatories can function as pivotal change-makers, including by advocating for and adopting measures for women’s direct participation and inclusion, including setting concrete targets and quotas, supporting implementing mechanisms and offering incentives.

Compact signatories have effectively led and supported mediation efforts driven by women leaders and women-led organizations in Burundi, Mali, the Niger and Sri Lanka. These efforts have yielded early results, showcasing the critical role of women in local mediation and conflict resolution.

Signatories intensified their actions in Africa, a continent with a high number of ongoing peace processes and the highest number of peacekeeping missions – 75 per cent of signatories took action in West and Central Africa and 74 per cent in East and Southern Africa.

65 per cent of signatories provided reporting on women’s participation pillar in 2023, a 7 percentage point decline from 2022.

According to The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024,[11] the number of forcibly displaced people reached an unprecedented 120 million in May 2024, and civilian casualties in armed conflicts surged by 72 per cent in 2023 including from conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza and other Middle Eastern conflicts, Sudan and related conflicts in the Great Lakes and Horn of Africa region. 2023 was also the fifth consecutive year of declining global peacefulness[12]underscoring the worsening state of international conflicts and their severe impacts on vulnerable populations.

The Peace Talks in Focus 2023 report[13] identified 45 global peace processes and negotiations.[14] Africa has the highest number of peace processes at 18 (accounting for 40 per cent of the total), followed by Asia and the Pacific with 10 processes (23 per cent). Europe and the Americas each had six processes (13 per cent), and the Middle East had five (11 per cent). Meanwhile, several armed conflicts escalated, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Israel–Palestine, Mali and the Sudan. In Ethiopia alone, the conflict has resulted in over 100,000 deaths.[15] Third-party mediation played a crucial role in peace processes including in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and the Sudan.[16]

Despite evidence that women’s participation in peace processes contributes to more sustainable peace, their participation remains severely limited at all stages – from ceasefire negotiations to mechanisms established to implement peace agreements. In 2023, women were entirely excluded from delegations in formal peace processes in settings such as Ethiopia, Libya and Yemen. In peace processes (co-)led and/or supported by the United Nations, women’s participation as delegates, signatories, observers and mediators stood at 19 per cent. Addressing these gaps requires targeted measures that dismantles systemic barriers and advances women’s leadership and active involvement in peace negotiations, ultimately fostering sustainable peace and stability.

In 2023, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-Women) launched the “Women in Peace Processes Monitor” to address a long-standing challenge with data collection on women’s substantive roles in peace processes. Though there have been attempts to collect data, efforts have been ad hoc and do not sufficiently recognize the complexity of peace processes. The lack of data on women’s participation and roles in peace processes has implications for gender equality and peacemaking efforts. It not only limits accountability for governments, organizations and parties to conflicts for their commitments to include women in peace processes but also leads to missed opportunities to harness women’s unique experience, perspectives and expertise.

Signatories provided similar reporting on participation specific actions in 2023 as in 2022. There remain 11 specific actions that have received no reporting, leaving a gap in the achievement towards the intended impact of women’s equal and meaningful participation

Sudanese women leaders in Kampala, Uganda. © UN Women/James Ochweri

From 2022 to 2023, signatories forged significant pathways to promote women’s meaningful participation in peace processes. Trends in 2023 reflect the continuation of support for advocacy, programming, engaging and supporting local women’s networks and financial support. The financial support ranges from direct funding of specific initiatives to more flexible unrestricted regular resources that cover the basic operating infrastructure and strategic interventions for an organization.

Diverse actions aimed at supporting and strengthening women’s roles in peace processes and implementation mechanisms continued to be prioritized across signatories. For instance, Germany supported projects enhancing women’s participation in peace processes in the Middle East, including Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen. Switzerland provided technical support to women’s organizations in Colombia for the implementation of the “Paz Total” peace policy. In the Central African Republic, the United Nations Department of Peace Operations (DPO) enhanced the capacities of over 300 women leaders in conflict resolution, social cohesion and mediation, resulting in the establishment of 12 “Circles of Peace” to advance local peace initiatives. In addition, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan employed a multiplicity of measures – good offices, advocacy, training and expert engagement towards the implementation of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). As of December 2023, progress was evident in the implementation mechanisms of R-ARCSS. Women make up 33 per cent of the National Constitutional Review Committee members and 50 per cent of the Political Parties Council are women. However, women’s representation on the National Election commission was at 22 per cent.

Civil society organization signatories such as the GNWP, SFCG, the Women’s International Peace Centre (WIPC) and the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) played pivotal roles in programming, advocacy and capacity-building. They trained women leaders and local peacemakers in conflict resolution, mediation, preventive diplomacy and negotiation skills.

Academic institutions also played a vital role in advancing the WPS agenda through research and policy recommendations. The United Nations University Centre for Policy Research (UNU-CPR) conducted studies on gender dynamics in migration and peace operations across the Global South and provided policy recommendations on the impact of women’s meaningful participation in peacebuilding. Research by the Alfred Deakin Institute and the University of Stirling focused on enhancing women’s roles in peacebuilding in Iran and East Africa, respectively.[17]

The reported activities of Compact signatories reveal a strong trend towards leveraging strategic positions within the United Nations Security Council to advocate for women’s participation in peace processes. Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates co-chaired the Security Council Informal Expert Group on Women, Peace and Security. During its second Council presidency in June 2023, the United Arab Emirates invited six women civil society briefers to the Security Council to highlight the challenges faced by women and girls in Afghanistan, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gaza, Haiti, Mali, South Sudan and Syria. Notably, the United Arab Emirates, with backing from Japan, led the United Nations Security Council to adopt resolution 2681, which condemned Taliban restrictions on Afghan women. This resolution, co-sponsored by 91 countries, indicated that there was general agreement among Member States on the principles of women’s leadership and participation in Afghanistan. At the same time, concrete measures and commitments to women’s participation across peace processes remain elusive.

In 2023, Compact signatories demonstrated a strong commitment to leveraging diverse peace process tracks to ensure women’s meaningful participation. Emphasizing inclusive dialogue and trust-building at local and national levels, efforts from Switzerland in Lebanon highlighted the importance of multilevel engagement in peacebuilding. This involved facilitating dialogue between women political actors from fragmented parties and improving skills and opportunities for joint engagement to advance conflict prevention and social cohesion, thereby strengthening Track III initiatives.[18]

The United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) reported that in 2023, women participated as delegates, signatories, observers and mediators in four of six United Nations (co)led or supported processes.[19] As a whole, women represented, on average, 19 per cent of delegates, signatories, observers and mediators in peace processes (co-)led and/or supported by the United Nations. In Libya and Yemen, the negotiating parties’ delegations did not include women. The United Nations also supported indirect inclusivity mechanisms in places such as Iraq, Syria and Yemen. In 2023, one woman, the United Nations Representative to the Geneva International Discussions in Georgia Ayşe Cihan Sultanoğlu, was a United Nations lead mediator in peace processes (co-)led and/or supported by the United Nations, and women accounted for 40 per cent of staff on United Nations mediation support teams in the four peace processes (co-)led and/or supported by the United Nations.

In Libya, the United Nations DPPA reported that while women were not included in the 6+6 Joint Committee of the House of Representatives and High Council of State established to draft the electoral laws or in the 5+5 Joint Military Commission that monitors the implementation of the Ceasefire Agreement, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Libya held consultations with women political representatives, civil society leaders and activists to discuss the way forward on elections, and technical gender support and electoral support was provided to the 6+6 joint committee.

Through its national action plan (NAP), the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland conducted active projects supporting women’s engagement within informal, local-level peace dialogues and structures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Ukraine and Yemen. These initiatives aimed to enable women’s participation in peace and dialogue processes by taking specific actions at policy and political levels, demonstrating clear support for Track III processes.

Civil society organizations such as Karama in South Sudan and Sisma Mujer in Colombia advanced women’s rights and participation through policy and legislative advocacy. Karama empowered women Members of Parliament to advocate for women’s rights and representation in key peace agreement implementation processes. Sisma Mujer supported compliance with the gender measures of the Peace Agreement in Colombia and participated in international advocacy scenarios, including at the United Nations Security Council, reinforcing the critical role of civil society in promoting women’s leadership and participation in peace processes.

In places where there is no process, or where processes are frozen or blocked, the United Nations is supporting consistent and long-term engagement with women political and civil society leaders to inform efforts to open space for peacemaking and support local leadership for peace.

Out of five thematic areas, signatories allocated the third-highest funding (US$ 46.5 million) to participation in peace processes after financing. The trends in 2023 indicate a strong commitment to financial support as a crucial means to enhance women’s participation in peace processes. This support spans from direct funding of specific initiatives, such as contributions from Ireland to peace dialogues in Colombia, to more flexible core funding provided by civil society organizations to women’s rights organizations.

Ireland provided US$ 110,000 as part of the countries pledge at the United Nations Peacekeeping Ministerial in December 2023, contributing to the United Nations DPO-led Accelerating Implementation of the Women Peace and Security Agenda project supportive of peace dialogues in Colombia. Ireland also allocated €100,000 to the Berghof Foundation to enhance the capacities of the Gestoría de Paz, a team of peace facilitators within the National Liberation Army, to strengthen women’s participation and environmental considerations during the peace process through strategic and technical support.

Civil society organizations, such as Women for Women International and Gender Concerns International, provided support to convene forums, sponsored women’s participation in meetings and flexible core funding to women’s rights organizations in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Yemen – empowering these organizations to meet their community needs and engage effectively in Track III peace processes.

Overall, the financial contributions in 2023 highlight the critical role of sustained funding in empowering women peacemakers and facilitating their meaningful participation in peace processes. This robust financial commitment underscores the importance of continued investment to advance the WPS agenda globally.

Capacity-building and training are central to the efforts of Compact signatories. South Africa conducted training sessions for women in conflict resolution, mediation, preventive diplomacy and negotiations. In Libya, Germany promoted young women’s participation in local sociopolitical processes through skills development. The United Kingdom supported women’s involvement in civic dialogue processes in Afghanistan and the Sudan, guiding the framing of inclusive dialogue processes and working alongside civic groups as independent actors. In the Sudan, for example, the United Kingdom provided technical expertise on gender inclusion to the main civilian political coalition, which has resulted in collaboration with 200 women to shape a national conference aimed at finding a political solution.

There is a clear trend of network building aimed at enhancing the agency and contributions of women in peace and security at both local and national levels. Regional organizations, such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), have been actively engaged in capacity-building programmes. In 2023, the OSCE launched initiatives like the Women’s Peace Leadership Programme and the Young Women for Peace Initiative, which are focused on empowering women and young women in leadership roles. United Nations DPO in partnership with the African Women Leaders Network (AWLN), UN-Women, the African Union, and FemWise-Africa convened a high-level event on regional challenges to women’s equal and meaningful participation in formal peace processes, conflict prevention and peacebuilding.

Civil society organizations, like SFCG, supported women’s roles in decision-making bodies. In Mali, women from the commune of Sadiola were not allowed to participate in resolving local conflicts and were excluded from peacebuilding efforts. Their participation in leadership development and training led to a change in the perception and attitude of local male leaders about women’s contribution to media platforms and conflict resolution processes. By the end of the programme, local women peacemakers led conflict resolution initiatives, including for conflict related to the management of mining sites. Programmes supporting women as mediators in Burundi and the Niger have enabled them to now engage independently in conflict mediation, leading to the successful resolution of 20 conflict cases, involving the dedication of 63 mediators and 414 community members who contributed over 3,000 hours of their own time. WPS localization workshops, led by GNWP in Papua New Guinea, resulted in the establishment of 18 Local Steering Committees in Dumbola, Jimi, Kakinjep, Kisu, Konum, Kugak Ward, Mollca, Mapowa and Mopwa wards to facilitate the integration of WPS resolutions into the region’s existing conflict resolution and peacebuilding mechanisms.

In 2023, there was a decline in the reporting on women mediator networks compared to 2022, but signatories continued to support networks. Notably, countries of the Ibero-American region established the Ibero-American Network of Women Mediators with Mexico serving as its inaugural president. Signatory actions included funding from Australia to the Southeast Asia Women Peace Mediators and the Pacific Women Mediators Network and support from Germany to FemWise-Africa. The United Kingdom provided support to women peacebuilding and mediators through the Women Mediators Across the Commonwealth which brings together 50 conflict mediators from all Commonwealth regions. For example, Women Mediators Across the Commonwealth members from West Africa are collaborating with women and communities in the Niger to develop innovative solutions for resolving and preventing conflict and sustaining democracy. This continued investment in women’s leadership in mediation highlights the crucial role of sustained support and targeted initiatives in fostering an inclusive and effective peacebuilding process. The Women’s Alliance for Security Leadership lead by the International Civil Society Action Network expanded membership with over 100 individuals representing 74 women peacebuilding organizations from 42 countries.

Civil society organizations represent 60 per cent of signatories who reported on women’s meaningful participation.

CSO: civil society organization; MS: member states; UN: United Nations entities; Acad: academic/ research institution; RO: regional organization

While advocacy efforts are well-documented, there is less information on the measurable outcomes of these initiatives. The 2024 WPS-HA Compact Accountability Report highlights meetings and resolutions passed, but there is limited information on the tangible impacts of these actions on the ground. More importantly, there is a lack of detailed outcomes regarding women’s inclusion and meaningful participation. This includes the underrepresentation of women in negotiation teams, the appointment of women lead mediators in formal peace processes, and the incorporation of gender-specific provisions in peace agreements. Such provisions are crucial to addressing gender inequality, recognizing the distinct impact of conflict on women, and responding to the specific needs of women and girls in post-conflict contexts. Additionally, there is a missed opportunity to harness these processes for transformative change that benefits women and children. In 2023 these ongoing challenges have been highlighted, underscoring the need for more concerted and targeted efforts to achieve gender equity in peacemaking.

This gap highlights the need for a more outcome-focused approach to ensure that policy commitments translate into real-world changes. Positively, the United Nations committed in 2023 to advocate for a minimum one third of women in mediation and peace processes while continuing to aim for an increase towards a 50:50 gender balance in political and electoral processes.

The 2023 reporting also exposes a sobering reality: despite a quarter-century of commitments under the WPS agenda, progress has stalled on this core element of the work. While initiatives like advocacy and capacity-building are important, the report reveals a critical gap. Signatories are focused on reporting programming activities, conducting research, highlighting financial commitments and offering training – but failing to deliver concrete results on specific Compact commitments for women’s meaningful participation in peace processes. This approach is not sufficient to change the status quo and fails to dismantle the power structures that continue to exclude women.

The glaring absence of women from key talks in ongoing conflicts underscores the urgent need to move beyond simply supporting efforts for women’s meaningful participation. A change in thinking is required – ensuring women’s leadership and active voice at the peace table.

1 Uphold mandates for women’s full, equal and meaningful participation in peace processes: Intergovernmental structures like the United Nations, European Union, African Union and Regional Economic Communities must support measures and intensify efforts to uphold mandates to transform women’s exclusion in peace processes ensuring gender equality as a key agenda item. They should match or exceed the commitment from the United Nations to advocate for and support an initial minimum target of one third of participants in mediation and peace processes being women while aiming for parity.

SIGNATORY

Search for Common Ground

In western Mali, locals remember when the water in the Faleme River turned from clear to murky orange. The toxic waste from nearby gold mines did not just contaminate the local environment, it also turned communities against each other in a fierce struggle over scarce natural resources.

While Mali ranks as Africa’s fourth-largest gold producer, the benefits of this wealth rarely reach the local population. Instead, communities are left grappling with the toxic aftermath: polluted rivers, land disputes and widespread poverty. Conflicts often turn violent, serving as stark reminders of the tensions simmering beneath the surface.

In response, SFCG, launched a project aimed at breaking the cycle of conflict in the mining regions of Mali. The initiative focuses on including women and youth – two groups often sidelined in decision-making processes – to lead peacemaking efforts in their communities.

Peace clubs were set up across four regions, bringing together community members from diverse backgrounds and across generations: youth, elders and local authorities. They also intentionally include 50 per cent women, who make up nearly half of the artisanal gold mining workforce but are often excluded from leadership roles.

Wanting to spread conflict resolution techniques further, the clubs jointly selected 3,000 participants for training in resolving disputes and rebuilding communal trust. Among them were 1,500 young people between 12 and 17 years of age and 1,500 between 18 and 35 years of age.

The inclusive and intergenerational aspects of the peace clubs in Mali, as well as their focus on training local peacemakers, intentionally aligns with the Compact’s principles of transformation, staff members say.

The peace clubs have already begun to make a tangible difference. Women, many of whom have had little to no formal education, are now participating

in decision-making processes for the first time. They are learning skills in conflict mediation and leadership and gaining the respect of their communities.

“We visit conflicting parties to prevent further tragedy and raise awareness,” says Sylvie, a Peace Club member in Bamako, “I want to open up the discussion on acts of violence, so they do not happen again.”

Their inclusion was an immense challenge in a country that ranks 137 out of 145 countries for gender equality. [19]

“There was fear in promoting women’s participation in decision-making, even among local staff,” said M’bara Adiawiakoye, SFCG’s Interim Country Director in Mali, “If you ask local leaders who to involve in conflict resolution, their tendency is not to involve women. We have to go to the community with a clear direction for their inclusion.”These efforts have turned the peace clubs into symbols of hope in western Mali. They show that when women and youth are given the tools and opportunities to lead, they can help their communities navigate conflicts and work towards a more peaceful and equitable future.

Women and girls affected by conflict, crisis and displacement have attained increased economic security, autonomy and empowerment through improved access and control of the resources, skill sets, education and employment opportunities they need, breaking discriminatory social and legal normative barriers to women’s economic empowerment and autonomy, as well as meaningful input into economic planning and recovery, across the conflict and crisis spectrum.

Signatories reported the least on women’s economic security compared to other pillars and allocated US$ 7.1 million to implement their Compact actions.

A wide range of signatories including civil society organizations, Member States, the United Nations and regional organizations reported holistic,[20] forward-looking and transformational programming for women’s economic empowerment (WEE), during and after conflict. They facilitated access for marginalized and forcibly displaced women to networks and services to secure economic opportunities and rights.

Compact signatories demonstrated a strong commitment to sharing knowledge and evidence with diverse stakeholders on effective strategies and interventions for WEE, during and after a crisis, despite the low level of reporting. This included documentation of good practice examples of women-owned and women-led social enterprises and businesses taking part in post-conflict economic recovery and economic revitalization and advocating for increased investment in these models.

million was the amount spent by signatories on economic security implementation.

35 per cent of signatories provided reporting on the economic security pillar in 2023, a 6 percentage point increase from 2022.

Reporting on economic security pillar represents 15 per cent of all reporting received on the Compact Framework, a 5 percentage point increase from 2022.

Escalating climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation are further pushing fragility

Signatories provided similar reporting oneconomic security specific actions in 2023 as in 2022. There remain 10 specific actions that have received no reporting, leaving a gap in the achievement towards the intended impact of economic security.

In 2023, signatories contributed significant actions to improve women’s economic security, access to resources and other essential services across all regions and framework areas. The trends show the continued support for programming, finance and policy in these fields with a strong intersectional approach, as well as the sharing of successful models for implementation through advocacy and the production of evidence. This pillar remained the least reported with a slight increase from 153 specific actions reported in 2022, to 157 in 2023. Signatories allocated US$ 7.1 million to implement their Compact actions.

Civil society organizations and Member States represent over 85 per cent of signatories who reported on women’s economic security.

MS: member state; CSO: civil society organization; UN: United Nations entity; Acad: academic/ research institution

SIGNATORY

ZANZIBAR SEAWEED CLUSTER INITIATIVE

Product diversification is another tool to promote economic security. Seaweed, once sold raw at low prices, is now being ground into powders or transformed into higher value goods such as soaps, lotions and food supplements. According to Msuya, a kilo of dry seaweed can earn up to US$ 0.25 profit. But by training women to grind it, the powder can earn them up to US$ 8 per kilo, while cosmetic products can sell from US$ 2 to US$ 10. The Compact’s principles of transformation informed the bedrock of their strategy, Msuya adds. The initiative promotes localized, intergenerational leadership by giving Zanzibari women of all ages a voice in the conversation about the future of their island and their industry. “However, if there is one principle of transformation from the Compact that we stand by, it’s inclusive and multi-stakeholder,” Msuya said.

The initiative brings together a diverse range of partners including research institutions driving innovation to government bodies shaping policy and businesses across the seaweed supply chain. This holistic approach ensures that every link in the chain – farmers, processors, exporters – is engaged and invested in the shared goal of building climate resilience and sustainable livelihoods for Zanzibar’s women seaweed farmers.

Msuya also credits the Compact with helping to bring the initiative’s work to the global stage, as it looks to find new partners and share their knowledge and innovation. “Being a part of the Compact makes our work visible,” Msuya said.“ But even more than that, it’s a checkpoint. It means that you check to see if you achieved what you originally set out to do.”

million was the amount spent by signatories on women’s participation.

51 per cent of signatories provided reporting on the leadership pillar.

Reporting on leadership represents 19 per cent of all reporting received on the Compact Framework, a 5 percentage point increase from 2022.

The ongoing situation in Afghanistan and Iran, where women and girls are denied their fundamental rights such as movement, education and employment, alongside the high levels of SGBV experienced by women in the Sudan, Haiti and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, overshadows some of the gains seen in women’s leadership globally. As of June 2024, there are 27 countries currently led by a woman, and there are only 15 countries in which women hold 50 per cent or more of the positions of Cabinet Ministers leading policy areas. Currently, 113 countries have never had a woman as Head of State of Government, and seven countries have no women represented in their national governments at all.[47] Currently, there are 110 Member States with NAPs on WPS.[48] Additionally, there are 16 Member States that have adopted Feminist Foreign Policies. All Member State signatories to the Compact have a NAP in place and four have adopted Feminist Foreign Policies to promote gender equality in humanitarian actions and women’s leadership in conflict prevention, resolution and peacebuilding.[49],[50]

In diplomacy, as of January 2024, 25 per cent of Permanent Representatives to the United Nations in New York are women, 35 per cent in Geneva and 33.5 per cent in Vienna. In the humanitarian sector, 69 per cent of crisis contexts in 2022 reported consultation with at least one local women’s organization marking an improvement in previous years. In the security sector, women comprise 6.5 per cent of military contingents in United Nations peacekeeping operations. Out of 12 peacekeeping mandates in operation in early 2024,[51] eight have gender units with a total of 44 gender advisers or officers currently serving across all mandates. The United Nations Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy calls for doubling the number of women in uniformed peacekeeping operations by 2028, with a target of 15 per cent for military contingents, 25 per cent for military observers and staff officers, and 30 per cent for Individual Police Officers and 20 per cent for Formed Police Units.

Signatories provided similar reporting on leadership specific action in 2023 and in 2022. There remain 11 specific actions that have received no reporting, leaving a gap in the achievement towards the intended impact of women’s leadership

Women’s leadership is a pre-requisite for achieving just and lasting peace and when women are in leadership positions, they have greater opportunities to participate in peace negotiations, mediation and peacebuilding processes. In 2023, WPS-HA Compact signatories made critical contributions to realizing global goals for gender parity in government and security sector leadership, and across the humanitarian-development-peacebuilding sectors.

Actions to promote women’s leadership in this reporting period were impacted by active war and conflict which were made more complex in the context of climate change and pandemics. Sixteen signatories reporting on leadership indicate that their work intensified due to conflict and crisis and reported shifts towards actions in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Ukraine and refugee-hosting countries due to the outbreak of war without prior commitments to actions in these countries. Eight signatories subscribing to leadership actions report removing or reducing bilateral programming due to conflict, particularly in Afghanistan, the Occupied Palestinian Territory and the Sudan.

In Afghanistan, signatories report adapting actions in response to increasing restrictions against women’s leadership. For example, GNWP implemented a cash assistance programme to continue supporting the families of 50 women staff who were banned from working. Similarly, Vital Voices’ GNRE Afghanistan Programme launched two subawards aimed at enabling Afghan women leaders to establish for-profit and advocacy organizations outside of the country.

New advocacy strategies aim to influence action among national governments and international actors. In Ukraine, WO=MEN reports continuing advocacy efforts to increase women’s leadership in decision-making on the protection of CRSV survivors and continued supporting dialogues among national actors and local women-led organizations to ensure gender-responsiveness in humanitarian action and women’s leadership in the recovery and reconstruction of Ukraine. Similarly, Karama, a civil society organization whose implementation was impacted by the conflict in the Sudan, reports progress through amplifying the advocacy of Sudanese partners by launching the Advocates for Women and Security Forum and reissuing operational guidance on the integrated implementation of WPS resolutions and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Signatories representing academic institutions and civil society organizations report that facilitating exchanges of knowledge and best practices with decision makers in government and United Nations agencies is a priority. However, while some indicate barriers to effective cross-sectoral communication, others report success in collaboration and partnerships to advance thought leadership.

Women’s leadership in disarmament and arms control led to enhanced coherence and coordination among United Nations entities in regions affected by ongoing conflict and high rates of GBV. The Informal Coordination Mechanism on Gender and Small Arms and Light Weapons convened to share updates between United Nations agencies and civil society organizations. UNDP and the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs joint initiative, the United Nations Saving Lives Entity, in cooperation with the Peacebuilding Fund and United Nations country teams, integrated a gender perspective into armed violence reduction activities in Cameroon, Jamaica and South Sudan. the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs implemented a multi-year project in support of the Programme of Action on Small Arms and Light Weapons, of which gender mainstreaming is a key pillar.

Despite advancements in policy, significant limitations in implementation inhibit women’s leadership in the security sector, and in United Nations country mandate operations. In 2023, Australia nominated Major General Cheryl Pearce for the second most senior military role in the United Nations as Deputy Military Adviser. However women’s representation in leadership in the military and other uniformed disciplines remains low. For example, prior to the withdrawal of United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the United Nations DPO supported women’s agency and leadership in transitional processes including through electoral sensitization, leadership workshops, and gender integration in political reforms, but the initiative was impeded by the abrupt closure of mission and reduced resources. Similarly, in United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), the United Nations DPO supported initiatives to increase women’s leadership and participation in electoral processes, leading to 51 per cent female voter registration and the election of the first woman Prime Minister. Following the drawdown and reconfiguration of MONUSCO, these initiatives risk reversal and require national leadership commitments, continued staffing and funding to uphold women’s agency in decision-making, and ensure that the basic standards for protection and continued opportunities for women’s leadership are sustained.

Member State signatories reporting directly on their NAPs to implement United Nations Security Council resolution 1325 indicate progress through consultations and collaboration with women-led civil society organizations in the development of NAPs. Signatories further report sustaining support for women’s leadership in the development and implementation of NAPs through multi-sectoral partnerships and direct financing to women-led organizations. For example, the Austrian Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs partnered with the GNWP in developing and implementing WPS action plans with local women’s organizations in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kenya, Moldova, South Sudan, Ukraine and Uganda. The 2023 Strategy, WPS NAP and subsequent Implementation Plans of the United States of America are inclusive, multi-sectoral, and intersectional and take steps to ensure a localized, intergenerational, and humanitarian approach to ensure sustainability and equal access to resources. To fill gaps in the law, public policy and operational guidelines for non-governmental actors, 23 signatories developed new laws, plans, policies or organizational strategies relating to leadership. For example, in June 2023, the new Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Act (2022) of Sierra Leone came into effect. This new law prohibits discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation and gender identity in areas including public accommodations and facilities, education, federal funding, employment, housing, credit, and the judicial system and enforces a 30 per cent quota for women’s senior leadership in the private sector.

Notable successes in increasing women’s leadership in humanitarian action include the initiative in Ukraine from the OSCE to train 36 Gender Focal Points from the State Emergency Services as trainers on gender-responsive and disability-inclusive humanitarian action, thereby expanding leadership roles and opportunities in crisis response, and responding to the increasing need for women responders and protection experts.

Additionally, a consortium led by Saferworld, including the Gender Action for Peace and Security (GAPS) network, Conciliation Resources, University of Durham and Women’s International Peace Centre in the United Kingdom (UK) implemented a “call-down” facility for the Government of the United Kingdom that delivers expert technical assistance and support on the application of the WPS framework and gender-responsiveness in conflict, security and crisis contexts across the whole government. This initiative also facilitates documentation of best practices and knowledge-sharing of women’s leadership in the conflict and security sector, which it makes available through a website. The Equality Fund’s localized grant-making to grass-roots women’s organizations, including girls, LGBTIQA+ women and non-binary people, supports community-based humanitarian response and post-conflict recovery across the Humanitarian-Development-Peace (HDP) nexus in Kenya, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, the Sudan, Syria, Türkiye and Ukraine.

Direct funding to women-led organizations further supported signatories in integrating gender-responsive mental health and psychosocial support into crisis prevention and response mechanisms. A flexible grant from the WPHF Rapid Response Window allowed the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict to support women-led organizations in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in developing and implementing trauma-informed service interventions. Direct flexible funding also supported consultations with women and girls affected by conflict to identify effective strategies for increasing women’s influence in the peace process in the Fergana Valley and address mental health and psychosocial support mental health and psychosocial support as a core component of peacebuilding.

Gender in humanitarian action (GiHA) working groups further support women’s leadership in humanitarian coordination and response in 21 countries, 19 of which are (co-)led and/or supported by UN-Women. GiHA working groups provided training, networking and capacity strengthening to support 424 women-led organizations in leadership within humanitarian planning, decision-making and monitoring and accountability. In Colombia and Guatemala, GiHA working groups made way for women-led organizations to gain formal recognition and assume decision-making roles in crisis response planning for the first time. In 2022, where GiHA and gender working groups were active, a higher percentage (82 per cent) of crisis contexts reported having consulted local women’s organizations, compared to 29 per cent in 2021 without active working groups. In 2023, UN-Women supported the establishment of a GiHA working group in Ethiopia. Less than six months after the working group started providing technical support and guidance to the Ethiopia Humanitarian Country Team and humanitarian clusters, and upon rounds of consultations with local women’s organizations, the Humanitarian Country Team endorsed the proposal to further decentralize the national GiHA working group to subregions within the country.

The Feminist Humanitarian Network worked with its women’s rights organization members to showcase the impact of their leadership in crises, as a way of highlighting and pushing for support for equitable progressive social norms, attitudes and behaviours towards women and girls, and inclusive leadership of women. The Feminist Humanitarian Network also developed an approach to ensuring safe spaces within the network, which its members have been able to take into their organizations to ensure their organizations are better able to function in feminist ways that contribute to opening spaces to design campaigns to remove barriers to funding.

As President and host of COP28, the United Arab Emirates provided travel assistance to youth delegates on the condition of gender parity among attendants. This allowed young women to actively engage in United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations, including the COP28 Gender-responsive Just Transitions and Climate Action Partnership and the Declaration on Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace, contributed to the adoption of expanded gender references in the COP28 Declaration. The United Arab Emirates was led by a women-led and woman majority COP28 negotiations team (67 per cent), including the Chief Negotiator. Yet only 34 per cent of Party delegates at COP28 were women, the same as 10 years ago, and less than one in five heads of delegation (19 per cent) was a woman.

CSO: civil society organization; MS: member states; UN: United Nations entities; Acad: academic/ research institution; RO: regional organization

Advancements in women’s leadership are being made through multi-sectoral partnerships that bring together actors in humanitarian response, conflict prevention and peacebuilding. Signatory reporting proves that where women-led organizations receive direct funding for training and capacity strengthening, their influence in leadership at all levels generates durable results in gender-responsive action across the HDP nexus. However, these gains are continuously impeded by systemic discrimination, regression in women’s human rights and uneven implementation of protection mechanisms for women and girls in conflict and crises. It is therefore critical that Member States, United Nations agencies and international humanitarian actors institutionalize and enforce gender parity in leadership across all sectors.

Reporting on leadership highlights that across all contexts, advocacy efforts are resulting in increased women’s leadership in NAP implementation and key areas such as climate security. To meet targets for gender parity and gender-responsiveness across the HDP nexus, these efforts must continue to be supported through strong partnerships among civil society, Member States, United Nations agencies and regional organizations.

SIGNATORY

FOREIGN, COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT OFFICE (UNITED KINGDOM)

The United Kingdom government’s WPS Helpdesk is setting a standard for integrating gender into national security policy. Funded by the International Security Fund (ISF), the Helpdesk has evolved into a vital, free resource for departments across the Government of the United Kingdom, offering expert advice on issues ranging from international conflict resolution to domestic security challenges.

According to Elise Sandbach, Gender Officer for the ISF, the Helpdesk is more than just a consultancy service. It is a collaborative hub, uniting diverse organizations such as fellow Compact signatory GAPS, Saferworld, Conciliation Resources, the University of Durham, and the Women’s International Peace Centre (WIPC). This coalition ensures that the Helpdesk does not just provide technical support – supports the United Kingdom‘s implementation of the WPS agenda.

The Helpdesk also represents a significant shift towards inclusive leadership and the use of local expertise, aligning with two of the WPS-HA Compact’s core principles of transformation. This approach is quickly becoming a model for other nations navigating the complexities of gender-sensitive security.

Sandbach highlights the Helpdesk’s role in fostering meaningful partnerships with women’s civil society organizations. Responding to a request from the ISF Jordan team, the Helpdesk helped design a project that enhanced Jordanian women’s access to decision-making processes, earning praise from international partners, including UN-Women and the Jordanian National Commission for Women.

Over the past year, the Helpdesk has increased its reliance on local experts, with 12 involved in various projects, up from eight the previous year. This shift is not just about numbers; it is about impact. Local experts bring a deep understanding of their context, language and culture, providing insights that international consultants might miss, Sandbach says.

In Colombia, for example, the engagement of a local expert to conduct a gender and WPS analysis proved particularly impactful. The expert facilitated crucial conversations between the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and local civil society organizations, opening doors that had previously been closed.

While the Helpdesk’s impact is felt globally, its relevance at home is equally significant. Not just a tool for international peace and security, the Helpdesk has expanded its scope to include domestic security issues such as organized crime. This evolution reflects the broader understanding of the United Kingdom that it is not only vital to integrate gender into international security strategies, but domestic plans as well.

“It’s not limited to one area of government; it’s a resource for any department, from the Ministry of Defense to the Home Office” said Rebecca Ingram, Gender Adviser at the ISF. “We’ve seen increasing interest across the government as departments realize the value of incorporating a gender lens into their security strategies.”

The Helpdesk’s commitment to impact is reflected in its rigorous approach to monitoring and evaluation, adds Sandbach. After completing a task, the Helpdesk conducts immediate surveys to gauge user satisfaction, followed by a six-month follow-up to assess the long-term impact of its work. The results have been overwhelmingly positive, with over 99 per cent of government departments which commissioned the Helpdesk for support, reporting that the Helpdesk met their needs very well or extremely well.

As the Helpdesk enters its final year of operation under its current project scope, its focus remains on making a lasting impact. With ongoing projects in Ukraine and plans to work in Somalia, the Helpdesk is on track to achieve this goal. Beyond 2025, the lessons learned, and the partnerships forged through the Helpdesk will continue to inform and inspire efforts to localize and strengthen women’s leadership in peace and security initiatives worldwide.

million was the amount spent by signatories to implement protection specific actions.

37 per cent of signatories provided reporting on the protection pillar.

Reporting on protection represents 13 per cent of all reporting received on the Compact Framework, similar to the amount of reporting received in 2022.

Women-led organizations and WHRDs have been strongly committed to protecting women’s rights and fighting against GBV, including protecting survivors and documenting and reporting cases to hold perpetrators accountable. Despite the increased cases of SGBV and threats against WHRDs in 2023, funding remains low. Although GBV funding increased to over US$ 230 million in 2023 from US$ 191 million in 2022, the needs remain significantly unmet (over US$ 1 billion).[58] In some cases, such as Yemen, the GBV sector was the least funded in humanitarian aid, compromising service provision and the protection of survivors.[59] Despite women-led organizations leading efforts, during 2021–2022,[60] funds for women-led organizations were only 0.13 per cent of ODA[61], dropping to US$ 631 million from US$ 891 million in 2019–2020.[62]

Underreporting of CRSV remains a significant challenge, owing to fear of reprisals, stigma and social norms, among other factors

Signatories provided similar reporting on protection specific actions in 2023 as in 2022. There remain seven specific actions that have received no reporting, leaving a gap in the achievement towards the intended impact of the protection pillar.

From 2022 to 2023, signatories made significant strides in protecting and promoting women’s rights in conflict contexts. Although few actions have exceeded objectives, the progress compared to the year 2022 is visible. The support for protection and service provision to GBV (particularly CRSV) survivors, support of women-led organizations, protection of WHRDs, advocacy and awareness regarding GBV, and positive masculinities continued on a steady pace through 2023. This support ranged from direct funding of specific initiatives to more flexible core funding for strategic actions, primarily from Member States, the United Nations and civil society organizations. Academic organizations, however, achieved the fewest actions during 2023 within this thematic area of protecting and promoting women’s human rights in conflict and crisis contexts.

One of the areas where Member States signatories engaged the most was addressing GBV from a comprehensive, holistic and survivor-centred approach including the protection of survivors, but also the provision of a wide range of services including sexual and reproductive health, psychological, social and economic counselling and more.

Member States and Civil society organizations provided similar reporting on protection and promotion of women’s human rights, representing 38 per cent and 44 per cent, respectively.

MS: member state; CSO: civil society organization; UN: United Nations entity; Acad: academic/ research institution

SIGNATORY

AMANI INITIATIVE

Nixon credits the inspiration for founding the initiative to his family and close relatives, who were forced into early marriage and denied the chance to complete their education. As Nixon progressed in his education, he could not ignore the stark contrast between his path and that of the relatives and girls he grew up with – many of whom were already married with children by the time he reached university.

Changing this culture starts with engaging men and boys, explained Nixon. “Men are part of the problem, but they are also crucial to the solution. They are often the gatekeepers of the social norms we aim to change – like deciding when women get married and if they can own property,” he said.

One of the ways the initiative recruits men as change agents is by working with Boda Boda riders, motorcycle taxi operators who are often linked to cases of sexual violence. Some of these men are now helping to educate their peers, working to transform potential perpetrators into protectors and advocates for women and girls.

Nixon says his vision for ending the cycle of violence against women is deeply rooted in the Compact’s principles of transformation, particularly the focus on localized, inclusive, intergenerational leadership. “We’ve been intentional about ensuring our change agents include both women and men, elders and youth,” he explained. “We can’t rely solely on young people to end child marriage when it’s been prevalent for the last 100 years. We also need partnerships with older gatekeepers who understand how to change the structures of our communities.”

However, for the initiative to be successful, it is important to share lessons learned and exchange knowledge with other signatories. “Collaboration and learning from others has always been our strength and passion. That’s why we’re committed to the Compact – because its mission aligns with what we want to do,” he said.

In the wake of global peacefulness deteriorating, various stakeholders are increasingly recognizing the importance of collaboration between generations to address the complex challenges in the realms of gender, peace and security and humanitarian action. This is visible through a 91 per cent rate of reporting of the Compact signatories who have demonstrated recognition and engagement with youth in different issue areas.

The majority of the intergenerational implementation of the WPS-HA Compact actions were in the area of women’s full, equal and meaningful participation and inclusion of gender-related provisions in peace processes. Compact issue areas of financing the WPS agenda and gender equality in humanitarian programming, women’s economic security, access to resources and other essential services as well as protection and protecting and promoting women’s human rights in conflict and crisis had fewer instances of intergenerational reporting and possibly implementation. Most of these actions were implemented in the African continent and as a result of collaboration between different WPS-HA Compact signatories.

Civil society organizations remain the leading stakeholders in reporting on intergenerational implementation of their commitments (56 per cent), followed by Member States (20 per cent), United Nations agencies (10 per cent), Academia (4 per cent) and Regional Organizations (2 per cent). 34 Signatories from 81 have reported on the youth-specific actions of the Compact that they are signed on to. The remainder reported on indicators that involved youth or their progress within the intergenerational principle of transformation. On the other hand, no signatories reported on five of the youth-specific actions of the Compact, leaving the need for commitment and accountability to these actions stronger than before.

of signatory reporting incorporated or reference youth.

WPS-HA Compact and UN Women Asia-Pacific Regional Conference. © UN Women/Jack Taylor

Compact signatories have committed to the implementation of intergenerational action through different activities and strategies with the highest number of actions reported as being relevant to investing in the Compact pillar on women’s full and meaningful participation and inclusion of gender-related provisions in peace processes with reporting qualities of meeting expected progress or exceeding expected progress.

Many Compact signatories have implemented their intergenerational actions in locations that are listed among the least peaceful countries in the world ranked by the Global Peace Index.[1] These include countries such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Iran, Lebanon, Libya, the Occupied Palestinian Territory, the Philippines, the Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, the Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Uganda, Ukraine, Viet Nam and Yemen. No commitments have been made for two years in a row to the Compact action to develop and enact initiatives for intergenerational co-leadership in peacebuilding efforts and processes, mediation and negotiations, including documentation of these initiatives at the national and international levels.

Karama has been actively engaged in empowering women and youth leaders across various conflict-affected regions such as Lebanon, Libya, the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and South Sudan where it has supported the development of youth and young women leaders to actively participate in advancing the implementation of national peace processes. Karama has also strived to facilitate engaging with traditionally hard-to-reach demographics such as marginalized women and young members of civil society organizations representing geographical regions in conflict and crisis, women and girls in refugee and internally displaced communities, as well as in neglected urban and hard-to-reach rural areas. By promoting their engagement in international conferences, forums and processes, Karama has ensured they are included in feminist movements.

Establishing partnerships with youth-led and young women-focused organizations and networks to embed their priorities in the implementation of YPS and WPS agenda were among the most implemented areas of action. In West Africa, Réseau Paix et Sécurité Pour les Femmes de l’Espace CEDEAO (REPSFECO) have worked with partners to engage youth civil society organizations to promote their rights and advocate for youth inclusion in local peace and security action plans. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, GNWP worked with YPS coalitions and Young Women for Peace networks to localize the United Nations Security Council resolution 2250, integrating youth demands into local development policies. They also hosted a Young Women Leaders Global Dialogue with participants from Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Georgia, Indonesia, Lebanon, Myanmar, Nigeria, the Philippines, Rwanda, South Sudan and Ukraine. The event facilitated information exchange among young women leaders and gender equality allies, fostering cross-regional solidarity for WPS and YPS resolutions at the local level. In Afghanistan, GNWP partnered with the Afghan Youth Ambassadors for Peace Organization to implement a gender-responsive humanitarian response in Nangarhar Province.

Signatories reported many instances of research, data collection and advocacy conducted by young women on a variety of topics. Feminist organization Our Generation for Inclusive Peace engaged youth in peacebuilding through research publications, campaigns promoting equitable social norms and partnerships with youth-led organizations globally. They emphasized intergenerational partnerships and documented young women’s leadership contributions to peace and security in a wide array of areas. Hope Advocates Africa based in Cameroon shared knowledge and evidence with diverse stakeholders on effective strategies and interventions for enhancing women’s economic security. Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation used its research grant resources to hire two young women researchers from Iran with multi-year contracts, supporting their research on peacebuilding, which included intergenerational local aspects and local peacebuilding. Associação de Jovens Engajamundo advocated for the connection between WEE and their participation in peace processes and collaborated globally with feminist groups, grass-roots activists, governments and international organizations to influence data-driven policies. Members of this organization co-authored articles on youth perspectives regarding climate, SRHR and gender inequality. Their contributions include frameworks like the Gender & Climate Justice Framework.[2]

Recognizing the importance of engaging men and boys in intergenerational action for peacebuilding and humanitarian action, several signatories reported holding training sessions and awareness-raising initiatives in the framework of the WPS agenda for men and boys. In these trainings, signatories reported transferring skills such as reporting with a gender perspective and human rights approach, assistance to women victims of CRSV, cybersecurity and communication online to combat harmful online gender norms to men and boys.

In Libya, GIZ piloted a project to improve young women’s participation in local sociopolitical processes, promoting peaceful and gender-equitable coexistence. Investments from Switzerland offer significant support to organizations that engage in GBV activities, which may include youth-focused initiatives, yet the exact allocation of funds towards youth-specific actions is not detailed. The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund of the United Kingdom (now Integrated Security Fund), however, has collaborated with local women’s organizations, including those involving young women, across various contexts such as Egypt, Iraq, Mali, the Philippines and Ukraine. Through the Civil Society Fund, Irish Aid has supported Saferworld’s project peacebuilding from the ground up in Yemen since 2014, focusing on marginalized groups such as women and youth – however, no age-disaggregated data or exact details were reported for 2023.

Through the UNICEF Global Humanitarian Thematic Fund, youth-friendly funding was provided to youth organizations to address the needs of young people systematically in humanitarian responses. The WPHF successfully funded 456 WHRDs, including a substantial portion of young women aged 18–29, from 22 countries. Additionally, they provided support to 1,221 dependents of these defenders, highlighting their commitment to safeguarding those at the forefront of human rights and peace efforts.

The PBF allocated 47 per cent of its investments in 2023 towards gender equality and women’s empowerment, focusing significantly on women and youth engagement. The Youth Promotion Initiative for 2023 focused on youth participation in political processes and protection of civic space, which included significant work and support for the empowerment and equality of young women and young women leaders. Part of the annual GPI involved 12 projects, totalling US$ 20.5 million, aimed at increasing women’s engagement, which inherently includes young women, in natural resource management, climate change mitigation and adaptation. Pilots of the GPI 2.0 approach, with a focus on supporting local women’s organizations, were active in the Gambia, Haiti and the Niger, with additional pilots in Colombia, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guatemala, Liberia and South Sudan. These pilots often involved young women and promoted their roles in these initiatives.

Many Compact signatories have invested in network creation and development for young women to engage with different stakeholders, including in multi-stakeholder intergenerational action. UN-Women has been instrumental in promoting the inclusion of young women in peace processes across various regions, including the Middle East and North Africa. They supported the second cohort of the Young Women Peacebuilders programme, empowering 47 young women from 13 Arab countries and establishing the Young Women Peacebuilders Network.

Similarly, the AWLN has a dedicated Young Women Leaders Caucus, focusing on inclusive approaches and partnerships to enhance the visibility and influence of young women in humanitarian and peace processes. They conduct joint advocacy initiatives with youth peacemakers and collaborate with African Union and United Nations agencies to integrate youth perspectives. Working together with other Compact signatories, including United Nations agencies and Member States demonstrated AWLN’s true capacity in spearheading continental, multi-stakeholder and intergenerational action.

ACCORD and the WIPC made remarkable strides in forging and sustaining partnerships with youth-led and young women-focused organizations that led to advocacy networks and reaching the national level and regional mechanisms for change. Their collaborations included the Gender Is My Agenda Campaign network, where meetings and trainings brought together over 250 youth from various African countries. These gatherings provided a platform to discuss their roles in the African Continental Free Trade Area implementation and to advocate for their inclusion in policymaking processes. They also focused on the inclusion of women in peace and decision-making processes, women and youth inclusion in the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area and emphasized the urgent need for justice and peace for women victims of mass crimes, victims of CRSV and children of conflict-related rape.